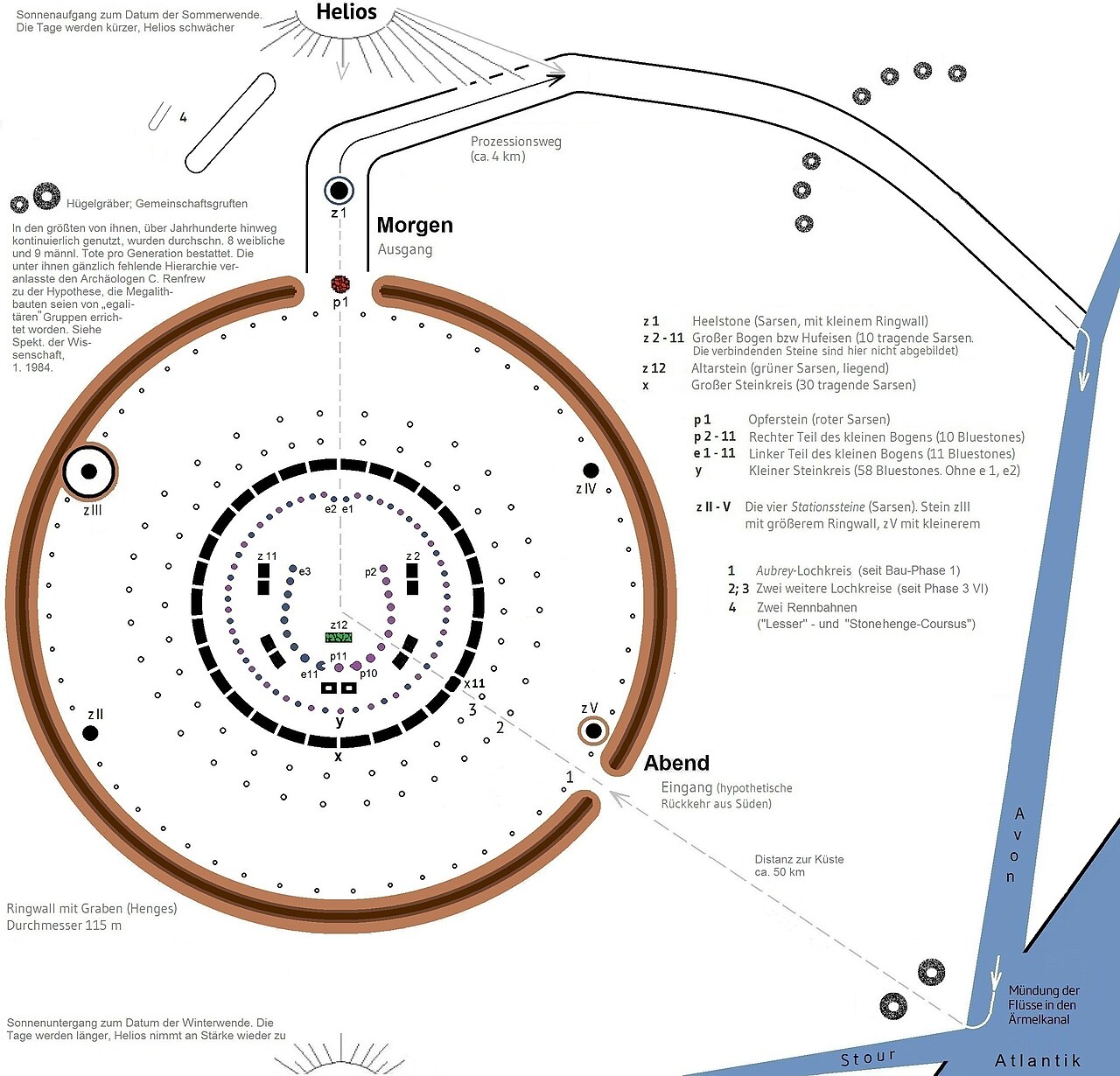

Standing on the windswept Salisbury Plain of southern England, Stonehenge is perhaps the world's most famous prehistoric monument and certainly its most debated — a circle of massive standing stones whose builders, purpose, and construction methods have fascinated scholars, mystics, and visitors for centuries. The monument was not built all at once but evolved through multiple phases of construction spanning approximately 1,500 years, from around 3000 BC to 1500 BC. The earliest phase consisted of a circular earthwork ditch and bank with 56 pits (the 'Aubrey holes') that may have held wooden posts or cremated human remains — Stonehenge began as a cemetery before it became a stone circle.

The most remarkable engineering achievement of Stonehenge's construction was the transport of its famous bluestones — 43 surviving stones weighing up to 4 tonnes each — from the Preseli Hills of Wales, approximately 240 miles to the west. Exactly how Neolithic people accomplished this feat, around 2500 BC, remains genuinely uncertain, though experiments suggest a combination of wooden sledges, rollers, and possibly rafts along the Welsh and English coast. The source quarries in Wales have been precisely identified at Carn Goedog and Craig Rhos-y-felin, and recent research suggests the bluestones may have stood at a stone circle in Wales before being dismantled and moved to Salisbury Plain.

The massive sarsen stones of the outer circle and the trilithon horseshoe — uprights of up to 25 tonnes topped by horizontal lintels — came from the Marlborough Downs 25 miles to the north. Raising these stones required the construction of earthen ramps, wooden levers, and an intimate knowledge of leverage that speaks to sophisticated Neolithic engineering knowledge. The lintel stones were carefully shaped with mortise-and-tenon joints on their undersides that fit over protruding tenons on the uprights, and curved along their length to maintain the circle — carpentry joinery translated into stone at enormous scale.

Stonehenge's alignment with the midsummer sunrise and midwinter sunset is deliberate and precise: on the summer solstice, the sun rises directly over the Heel Stone and its first rays strike the center of the monument. This astronomical orientation, combined with the enormous labor investment in its construction and the cremated remains of hundreds of individuals found at the site, suggests Stonehenge served as a ceremonial and religious center of extraordinary importance — possibly a place of ancestor veneration, healing, or solar ritual for communities across a wide region of prehistoric Britain.

Stonehenge was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1986, jointly with nearby Avebury. Recent decades have seen remarkable advances in our understanding of its builders: DNA analysis of individuals buried at Stonehenge shows a population that had migrated from Anatolia to Britain around 4000 BC, bringing farming with them. The people who built the later phases of Stonehenge show evidence of migration from the continent related to the Bell Beaker culture around 2500 BC. A long-debated tunnel to reduce traffic near the monument was approved in 2023, promising to restore the ancient landscape that once surrounded England's most enduring mystery.